Front Cover Back Cover

|

At the end of the war, the immediate family counted two victims-2 out of 10. The casualty rate for the entire Jewish population in France was 1 out of 4. Throughout Europe, the percentage of Jewish children among the deportees matched the percentage of children in the Jewish population, 23 percent, but in France, it was 14 percent.

Why was there this difference? It was not caused by Vichy’s mercy toward Jewish children, but because another France was watching, and because outside the country, the real France of General De Gaulle was fighting along with the Allies. The children were saved by the actions of the righteous, those who could not tolerate to witness their country breaking its traditions of honor and hospitality by delivering thousands of Jewish families to their worst enemies, who did not hide their criminal projects. Ruth/Renée’s story is the story of the rescue of the Jews. It is a personal story that embodies the collective story of the foreign Jews who escaped deportation and the gas chambers, when they so easily could have been denounced.

The story of Ruth is moving in its simplicity. Through hopes, terrors, reunions and separations, it is the story of a child who never forgot that she was Jewish; the story of many hidden children who were saved from the Holocaust, and of thousands of children who lived similar lives until the anti-Jewish hate caught up to them. The history and stories of these children hidden and lost are written in the two thousand pages of French Children of the Holocaust.

Serge Klarsfeld (New York: New York University Press, 1995)

* * * *

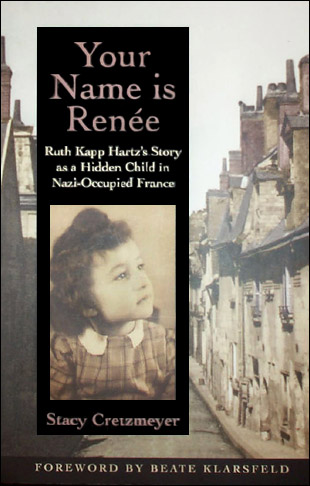

Author: Stacy Cretzmeyer

Foreword by Beate Klarsfeld

Ruth Kapp Hartz's Story as a Hidden Child in Nazi-Occupied France

softcover, 5.5 x 8.5 ins.

15 illustrations, annotated, references,238 pp.

Published by Oxford University Press,

distributed by Beach Lloyd Publishers, LLC

| Your Name is Renée | $12.95 |

Beach Lloyd Direct | |

| Amazon | |